|

| Photo of Joel Augustus Rogers aka J.A. Rogers (b. 9/6/1880 - d. 3/26/1966) |

What is known is that in 1906, after serving in the British Army at Port Royal, Jamaica, J.A. Rogers moved from Jamaica to Harlem, New York, where he would eventually reside during the majority of his adult life, living with his wife Helga M. Rogers. Rogers did make Black Chicago his home for a time, while working as a Pullman Porter and reporter.

In 1909, Rogers enrolled in the Chicago Art Institute. According to his biographer, Thabiti Asukile, he attended art classes there while supporting himself financially as a Pullman Porter, where he would work until 1919. As a result of his being able to travel widely within the United States as a Pullman Porter, Rogers was certainly able to access a wide variety of libraries that had developed in different cities across the country. A voracious bibliophile, Rogers compiled information about African history and began to write and self-publish his research findings.

"I found in Chicago a friend who introduced me to books in which I found the names of several great men of Negro ancestry past and present," states Rogers in his book World's Great Men of Color, Vol. 1. "In my spare time, and with no thought of writing a book, I began to collect some of these names. That was about 1911."

|

| Early photo of J. A. Rogers. |

Rogers served as a foreign correspondent for a variety of African American newspapers, especially after he moved to Harlem in 1921. In addition to his published works for the Chicago Enterprise and Chicago Defender newspapers, Rogers wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier and served as sub-editor for the Daily Negro Times -- the latter published by Marcus Garvey. The editors of the Pittsburgh Courier sent Rogers as a correspondent to cover the coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie I in Ethiopia. Additionally, Rogers was noted as the only Black U.S. war correspondent during World War II. He would publish widely in publications such as the New York Amsterdam News, the Messenger Magazine, and others -- making him one of the leading Black journalist of his times.

| |||

| Book published by J.A. Rogers -- 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro with Complete Proof |

| |

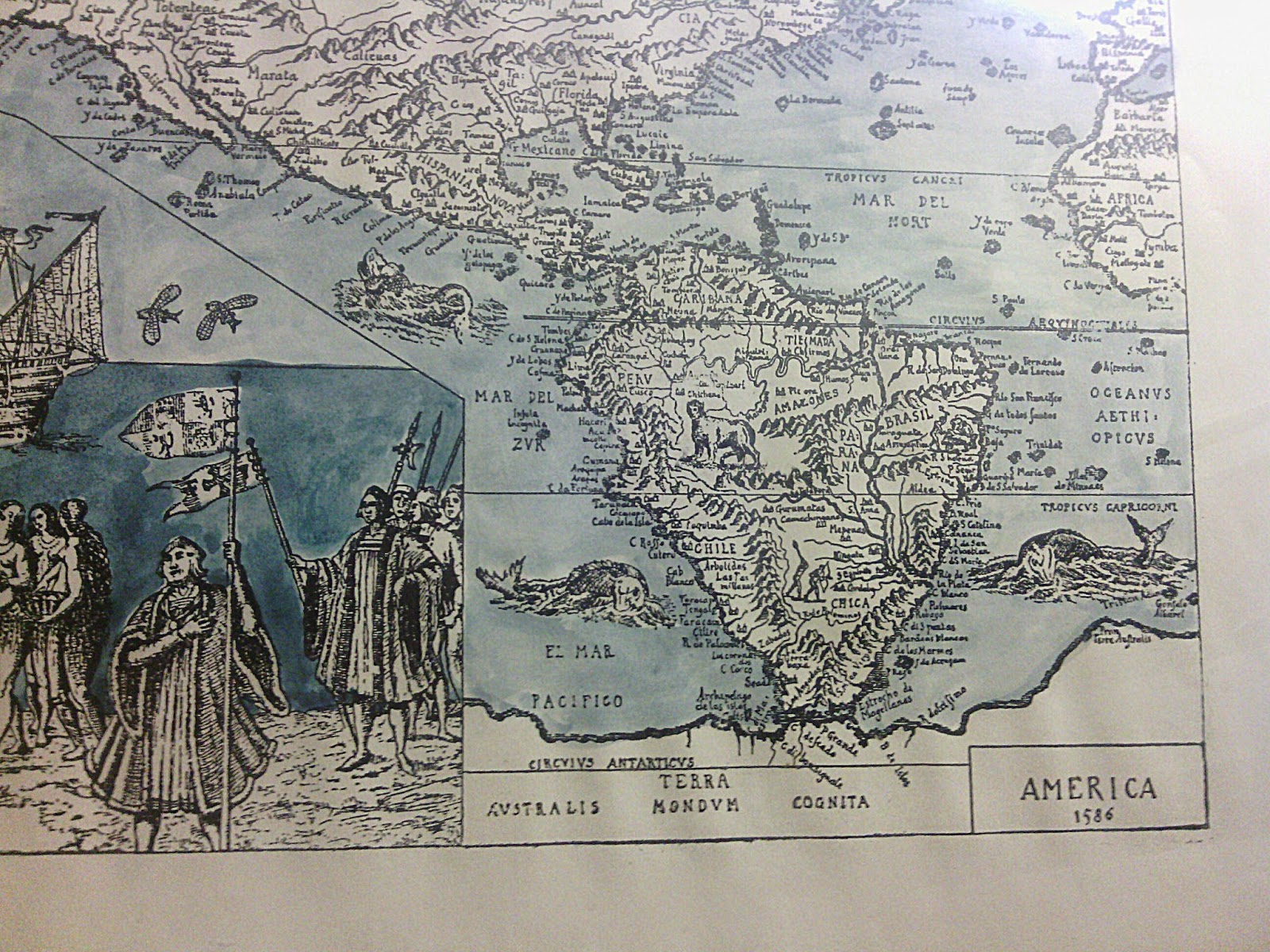

| Copy of an illustrated work J.A. Rogers published in newspapers and in books. Many of his amazing facts were substantiated by subsequent writings on the topic. For example, read more about Scota of Egypt and the origins of the Scottish people at "The pharaoh's daughter who was the mother of all Scots," from The Scotsman publication. |

The common thread in Roger's research was his unending aim to counter white supremacist propaganda that prevailed in segregated communities across the United States against people of African descent.The works of Rogers only became assigned reading in the most independently-developed, university curriculum of African-centered history professors -- and even then, after Rogers had passed away. The noted historian Dr. John Henrik Clarke states that Rogers "looked at the history of people of African origin, and showed how their history is an inseparable part of the history of mankind." His works have enlightened many people interested in uncovering the suppressed histories of African people. His legacy continues through the great volume of works he has left behind.

J.A. Rogers Works, Chronological by Publication Date:

- From "Superman" to Man. Chicago: J. A. Rogers, 1917. —novel.

- As Nature Leads: An Informal Discussion of the Reason Why Negro and Caucasian are Mixing in Spite of Opposition. Chicago: M. A. Donahue & Co, 1919. —novel.

- The Approaching Storm and Bow it May be Averted: An Open Letter to Congress Chicago: National Equal Rights League, Chicago Branch: 1920.

- "Music and Poetry — The Noblest Arts," Music and Poetry, vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1921).

- "The Thrilling Story of The Maroons," serialized in The Negro World, March–April 1922.

- "The West Indies: Their Political, Social, and Economic Condition," serialized in The Messenger (Volume 4, Number 9, September 1922).

- Blood Money (Novel) serialized in New York Amsterdam News, April 1923.

- "The Ku Klux Klan A Menace or A Promise," serialized in The Messenger (Volume 5, Number 3, March 1923).

- "Jazz at Home" The Survey Graphic Harlem, vol. 6, no. 6 (March 1925).

- "What Are We, Negroes or Americans?" The Messenger, vol. 8, no. 8 (August 1926).

- Book Review, Jazz, by Paul Whiteman." Opportunity: The Journal of Negro Life (Volume 4, Number 48, December 1926).

- "The Negro's Experience of Christianity and Islam," Review of Nations, Geneva (January–March 1928)

- "The American Occupation of Haiti: Its Moral and Economic Benefit," by Dantes Bellegarde. (Translator). Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life (Volume 8, Number 1, January 1930).

- "The Negro in Europe," The American Mercury (May 1930).

- "The Negro in European History," Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life (Volume 8, Number 6, June 1930).

- World's Greatest Men of African Descent. New York: J. A. Rogers Publications, 1931.

- "The Americans in Ethiopia," under the pseudonym Jerrold Robbins, in American Mercury (May 1933).

- "Enrique Diaz," in Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, vol. 11, no. 6 (June 1933).

- 100 Amazing facts about the Negro with Complete Proof. A Short Cut to the World History of the Negro. New York: J. A. Rogers Publications, 1934.

- World's Greatest Men and Women of African Descent. New York: J. A. Rogers Publications, 1935.

- "Italy Over Abyssinia," The Crisis, Volume 42, Number 2, February 1935.

- The Real Facts About Ethiopia. New York: J.A Rogers, 1936.

- "When I Was In Europe," Interracial Review: A journal for Christian Democracy, October 1938.

- "Hitler and the Negro," Interracial Review: A Journal for Christian Democracy, April 1940.

- "The Suppression of Negro History," The Crisis, vol. 47, no. 5 (May 1940).

- Your History: From the Beginning of Time to the Present. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Courier Publishing Co, 1940.

- An Appeal From Pioneer Negroes of the World, Inc: An Open Letter to His Holiness Pope Pius XII. New York: J. A. Rogers, 1940.

- Sex and Race: Negro-Caucasian Mixing in All Ages and All Lands, Volume I: The Old World. New York: J. A. Rogers, 1941.

- Sex and Race: A History of White, Negro, and Indian Miscegenation in the Two Americas, Volume II: The New World. New York: J. A. Rogers, 1942.

- Sex and Race, Volume III: Why White and Black Mix in Spite of Opposition. New York: J. A. Rogers, 1944.

- World's Great Men of Color, Volume I: Asia and Africa, and Historical Figures Before Christ, Including Aesop, Hannibal, Cleopatra, Zenobia, Askia the Great, and Many Others. New York : J. A. Rogers, 1946.

- World's Great Men of Color, Volume II: Europe, South and Central America, the West Indies, and the United States, Including Alessandro de' Medici, Alexandre Dumas, Dom Pedro II, Marcus Garvey, and Many Others (New York: J. A. Rogers, 1947).

- "Jim Crow Hunt," The Crisis (November 1951).

- Nature Knows No Color Line: Research into the Negro Ancestry in the White Race. (New York: J. A. Rogers, 1952).

- Facts About the Negro. (Drawings by A. S. Milai) (booklet) (Pittsburgh: Lincoln Park Studios, 1960).

- Africa's Gift to America: The Afro-American in the Making and Saving of the United States. With New Supplement Africa and its Potentialities. (New York: J. A. Rogers, 1961).

- She Walks in Beauty. Los Angeles: Western Publishers, 1963. —novel

- "Civil War Centennial: Myth and Reality," Freedomways, vol. 3, no.1 (Winter 1963).

- The Five Negro presidents: According to What White People Said They Were. New York: J. A. Rogers, 1965.